Tibet literature: a vast treasury mostly unexplored

From the eighth century onwards, Tibet was thus a privileged receptacle of all the Buddhist teachings. Most Buddhist countries adopted traditions in which either the Theravada or the Mahayana teachings, but not both, predominated. The particularity of Tibetan Buddhism is to include both, and moreover to be the only country outside India in which the Vajrayana (or Mantrayana) teachings—based on the tantras—were widely studied and practised (although some Vajrayana traditions survived in Nepal and a limited Vajrayana tradition reached Japan). Since many texts were taken from India to Tibet at different periods of Indian Buddhism, and continued to be preserved there when they had been lost or destroyed in India, the literature of Tibet contains the largest collection of sutras, tantras and shastras anywhere in the world.

The Tibetans, therefore, preserved all aspects of Indian Buddhism intact from the eighth century to the twentieth. But this was far from a mere static preservation of sacred treasures. The Buddhadharma was the main preoccupation of Tibet’s best minds for centuries, giving rise to an extraordinary range of philosophical, poetic, academic and inspirational literature (as well as a distinctive and magnificent artistic and architectural heritage). As great masters studied, practised and accomplished the Buddhist teachings in all their myriad methods and approaches, they recorded their insights and discoveries in commentaries to the scriptures, in liturgies, in poems and songs of realization, in systematic surveys of the path, and in profound pith-instructions. Debates between masters and traditions on the finer points of meaning led to texts of extraordinary depth and scope on a huge range of philosophical and contemplative points.

Taranatha

One might imagine that Tibet’s greatest glories belong to the remote past, and that recent centuries represent a period of decline, but this is by no means the case. In fact each century (including the twentieth) and each generation has produced its share of spiritual giants. To name but a few: Atisha, Rongzom, Marpa, Milarepa, Gampopa and Padampa Sangye in the eleventh and twelfth; Sakya Pandita in the thirteenth; Butön, Thangthong Gyalpo, Longchenpa and Tsongkhapa in the fourteenth and fifteenth; Ngari Panchen, Taranatha, the Fifth Dalai Lama and Terdak Lingpa in the sixteenth and seventeenth; Shabkar, and Jigme Lingpa and his disciples in the eighteenth. The nineteenth century saw a particular kind of renaissance in the ri-med or non-sectarian movement, inaugurated by Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo, Jamgön Kongtrul and others, which sought to break down the barriers that had crystallized between the different Buddhist schools by studying and teaching them all impartially, and writings by the profusion of great masters who followed such as Patrul, Mipham, Jigme Tenpai Nyima, the third Shechen Gyaltsab, and many others, as well as those of inspired tertöns like Chokyur Lingpa and Dudjom Lingpa, constitute an extraordinary flowering of Tibetan Buddhist thought which continued unabated through the first half of the twentieth century. Indeed, despite the unimaginable upheaval caused by the invasion of Tibet, many accomplished scholars, including Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche and Dudjom Rinpoche, continued to contribute to Tibetan literature in exile.

Finally, a survey of Tibetan literature would be incomplete without mention of the ever-increasing body of secular writing—novels, drama, history, political and social commentary, journalism—both from the diaspora and from within Tibet, that bears witness to Tibetan culture’s encounter with the modern world and the continuing strength of a deeply rooted tradition.

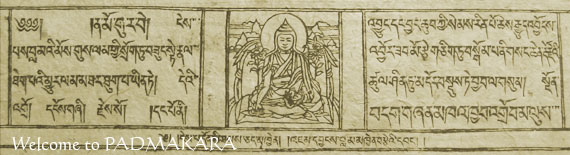

Rare Tibetan manuscript,

preserved by Padmakara

This great treasury has, for the most part, miraculously survived the ravages of the last sixty years, but many rare texts and manuscripts are still in danger of disappearing, and many have still not been recovered. Tibetan literature is for the most part unknown to the rest of the world, and only a very small portion of it has been translated into other languages—while the living tradition of oral transmission so necessary for correct interpretation of the texts could disappear completely in one more generation. Padmakara and Songtsen’s programmes are aimed at action on several aspects, as described in the section preserving rare & endangered books.

Tibet, its language & its literature: