The history of Tibet's unique literature

Padmasmambhava

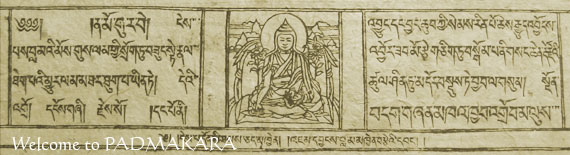

The story of how Tibet became a repository of the Buddhist teachings and traditions from the seventh century right through until the twentieth (surely one of the most extraordinary in the history of human culture) shows it to have been far from simply a lucky accident. It began with the pioneering foresight of the great seventh century King Songtsen Gampo and his minister Thönmi Sambhota, who adopted a new alphabet of Indian origin and elaborated the grammar of the Tibetan language, allowing the first translations to begin. But it was some 120 years later, in the eighth century, that the major work of establishing Buddhism in Tibet and translating the Buddhist canon began in earnest. At the request of King Trisong Detsen, the great master Padmasambhava and Shantarakshita established the first university, called Samye, in central Tibet. Padmasambhava and Shantarakshita, with Vimalamitra and over a hundred specially invited Indian scholars, trained Tibetan translators such as Vairotsana, Kawa Peltsek, Namkhai Nyingpo, Langdro Könchok Jungne, Kyeuchung Lotsa and others, and systematically set about the immense task of translating most of the texts of what now comprise the Kangyur and Tangyur, containing respectively the Buddha’s own words (in some 100 volumes), and the commentaries of the subsequent great Buddhist philosophers and masters of India (in some 225 volumes).

A huge number of these texts were translated by this first generation of Tibetan translators over a relatively short time, although new translations continued to be added to these great collections, until the fourteenth century in the case of the Kangyur (when its content list was finally laid down by Butön) and until the seventeenth century in the case of the Tangyur (which was settled in its present form during the reign of the Great Fifth Dalai Lama). Other translated texts from India were gathered together in different collections, and from the time of Padmasambhava onwards, as Buddhist practice and scholarship spread and flourished in Tibet, the great Tibetan masters and scholars taught and recorded their experience and profound knowledge, adding to the ever-increasing body of Tibetan literature. While a large majority of writings concentrated on Buddhist philosophy and practice, traditionally classified as ‘inner science’ or metaphysics, the scope of both translated and indigenous Tibetan literature is vast, covering a wide range of subjects, classified into the other four major sciences (medicine, technology and the arts, grammar, and logic) and the five minor sciences (astrology, poetics, prosody, and drama).

Meanwhile, outside Tibet, and notably in India as it underwent successive waves of invasion and social change, much of the original literature had long been irretrievably lost, and the living traditions interrupted. By the early thirteenth century, the great Buddhist monastic university of Nalanda (which had been a flourishing centre of learning for eleven centuries) and the newer universities of Vikramashila and Odantapuri had all been destroyed as the Mughal invaders swept through India. The arrival of Islam and political changes in Indian society had driven the Buddhadharma from its land of origin, and it was in other countries that the teachings were preserved—the Theravada in Sri Lanka, Burma, Thailand and Cambodia, the Mahayana in China, Japan, Korea and Indochina, and the Vajrayana mainly in Tibet. Tibet was doubly fortunate. Not only was it one of the few countries in which the Vajrayana continued to be practised, it was also the only one in which the full range of teachings, from all three traditions, was transmitted and preserved.

Tibet’s own history was not exempt from upheavals and political changes, but a combination of its geographical isolation, and the profound respect felt over the centuries by its inhabitants for the sacred texts, ensured the survival and evolution of this uniquely rich body of culture, knowledge and wisdom, combining the intact legacy of Indian Buddhist thought with the deep insights and experience built up by so many generations of Tibetans dedicating themselves entirely to Buddhist study and practice, over almost thirteen centuries.

Extraordinarily long though it was, this cultural continuity was to be tragically and brutally interrupted. Starting in 1949, and completed ten years later, the Communist invasion and occupation of Tibet led to the death of over 1 million Tibetans. Among them, and particularly targeted, were thousands of the most learned scholars and accomplished masters, who were imprisoned, tortured and killed. Most of the major libraries and monasteries were totally destroyed. Many of these libraries contained the last remaining texts of their kind in the world, their Sanskrit originals having been lost or destroyed. In all, a devastating number of Tibetan texts was destroyed. Some are now completely lost.

Just one example is the library of Riwoche monastery, among whose treasures were the rarest ancient Indian manuscripts, rescued in the thirteenth century by Sönam Pal from the universities of both Nalanda and Vikramashila during their destruction by the Mughal invaders. The library also housed a vast collection of unique translations of Buddhist teachings and the writings of great Tibetan scholars and masters. Indeed, the collection was so vast that only by the most arduous efforts could the Communist troops destroy it all. The fires were kept ablaze for months on end, until finally the very last of the books was annihilated.

Fortunately, however, despite the massive destruction of many such major libraries, not everything of Tibetan literature was lost. As the invasion began and it soon became obvious that Tibetan Buddhist culture was not going to survive in Tibet, among the hundreds of thousands of Tibetans who risked their lives to escape into the neighboring countries of Nepal, India and Bhutan, were numerous Tibetan scholars and masters carrying their precious texts. Many of them left behind all their valuable ornaments and possessions, choosing instead to bring as many books as could be carried on the rigorous journey across the Himalayas. It is thanks to their tremendous efforts that many precious texts survived destruction.

But even then their books were not in security, for another difficult period awaited them, in the precarious conditions of the early makeshift refugee camps. Gradually, the exiled lamas began to construct new settlements, monasteries and libraries. Thanks largely to the hard work of the U.S. Library of Congress’ representative in Delhi, Mr Gene Smith, the nineteen-seventies saw a wave of copying, reprinting and publishing of all the books that had been carried out of Tibet in the preceding decades. Catalogues began to be compiled, and it was possible to see more clearly what had survived and what was still missing. Later, starting in the nineteen-nineties and continuing still, computer input of many of the great collections of texts could be undertaken, further safeguarding them and rendering them more accessible. More recently still, it became clear that not only rare and precious manuscripts, but even texts reprinted in the seventies, were still being lost or were decaying in the damp conditions of some of the monasteries, and a new programme to saveguard them more rapidly by computerized scanning and archiving was set up by the Tibetan Buddhist Resource Center, again thanks to the foresight and encyclopaedic knowledge of Gene Smith.

In Tibet, the occupation continued, and even now Tibetans are far from free to adhere to their traditional culture. But as the fiercely destructive frenzy of the Cultural Revolution gradually abated, a few rare texts that had been hidden for decades to protect them from harm began, little by little, to reappear. Copies were brought out to India and Nepal, or in some cases re-published in Tibet itself or China. Scholars and researchers are still discovering, identifying and restoring works that everyone thought had been lost entirely.

The full wealth of Tibet’s literature will probably never be completely restored, but thanks to the extraordinary importance that Tibet’s scholars and lamas accorded their precious texts, a miraculous number of them have been preserved despite the catastrophe. Strenuous efforts must still be made to ensure their continuing survival—and to make them available to a world in sore need of the knowledge and wisdom they contain.

Tibet, its language & its literature: